For the last four years of doing my PhD at the TU Delft and the MAVlab, we were determined to figure out how to make a swarm/group of tiny quadcopters fly through and explore an unknown indoor environment. This was not easy, as many of the sub-challenges that needed to be solved first. However, we are happy to say that we were able to show a proof-of-concept in the latest Science Robotics issue! Here you can see the press release from the TU Delft for general information about the project.

Since we used the Crazyflie 2.0 to achieve this result, this blog-post we wanted to mostly highlight the technical side of the research, of the achievements and the challenges we had to face. Moreover, we will also explain the updated code which uses the new features of the Crazyflie Firmware as explained in the previous blogpost.

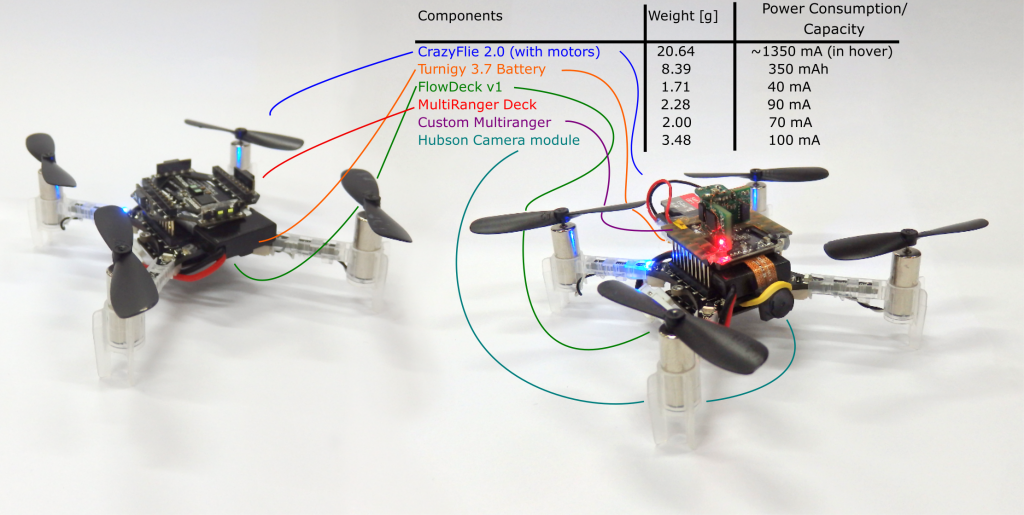

Hardware

In the paper, we presented a technique called Swarm Gradient Bug Algorithm (SGBA), which borrows (as the name suggests) navigational elements from the path planning technique called ‘Bug Algorithms’ (see this paper for an overview). The basic principle is that SGBA is a state-machine with several simple behavior presets such as ‘going to the goal’, ‘wall-following’ and ‘avoiding other Crazyflies’. Here in the bottom you can see all the modules were used. For the main experiments (on the left), the Crazyflie 2.0’s were equipped with the Multiranger and the Flowdeck (here we used the Flow deck v1). On the right you see the Crazyflies used for the application experiment, were we made an custom Multiranger deck (with four VL53L0x‘s) and a Hubsan Camera module. For both we used the Turnigy nanotech 300 mAh (1S 45-90C) LiPo battery, to increase the flight time to 7.5 min.

Experiments

With this, we were able to have 6 Crazyflies explore an empty office floor in the faculty building of Aerospace engineering. They started out in the middle of the test environment and flew all in different preferred directions which they upheld by their internal estimated yaw angle. With the multi-rangers, they managed to detect walls in their, and followed its border until the way was clear again to follow their preferred direction. Based on their local odometry measurements with the flowdeck, the Crazyflies detected if they were flying in a loop, in order to get out of rooms or other situations.

A little before half way of their battery life, they would try to get back to their initial position, which they did by measuring the Received Signal Strength Intensity of the Crazyradio PA home beacon, which was located at their initial starting position. During wall-following, they measured the gradient of the RSSI, to determine in which directions it increases or decreases, to estimate the angle back the goal.

While they were navigating, they were also communicating with each-other by means of broadcasting messages. Based on those measurements of RSSI, they could sense other Crazyflies approaching, which they first of all used for collision avoidance (by letting the low priority CFs move out of the way of the high priority CFs). Second of all, during the initial exploration phase, they communicated their preferred direction as well, so that one of them can change its exploration behavior to not conflict with the other. This way, we tried to maximize the explored area by the Crazyflies.

One of those experiments with 6 Crazyflies can be seen in this video for better understanding:

We also showed an application experiment where 4 crazyflies with the camera modules searched for 2 dummies in the same environment.

Challenges

In order to get the results presented above, there were many challenges to overcome during the development phase. Here is a list that explains a couple of the elements that needed to work flawlessly:

- Single CF robustness: We used the Flowdeck v1, for the ‘deadlock’ detection and the basic velocity control, which was challenging in the testing environment because of low lighting conditions and texture. Therefore the Crazyflies were flying at 0.5 meters in order to ensure robustness. The wall-following was performed solely using the Multiranger. This was tested out in many situations and was able to handle a lot of type of obstacles without any problem. However the limited FOV of the laser range finder can not detect all types of obstacles, for instance thin ones or irregular ones such as plants. Luckily these were not encountered in the environment the Crazyflies flew in, but to increase robustness, we will need to consider adding a camera to the navigational drive as well.

- Communication base-station. SGBA by essence only needs one base-station Crazyradio PA, since all the behavior is completely on board. However, in order to show results in the paper, it was necessary for the CF to communicate information back, like odometry, state and such. As this was a two way communication (CFs needed RSSI to get back) each Crazyflie needed 1 base-station. Also, they all needed to be on different channels to avoid package collisions and RSSI accumulation.

- Communication Peer to Peer. At development time, P2P didn’t exist yet, so we had to implement broadcast communication between the Crazyflies. Since the previous pointer required them to listen on different channels, the NRF had to be configured to send separate broadcast messages on all those channels as well. In order to time this properly, the home beacon had to sync the Crazyflies accordingly by sending out a timer. Even so, the avoidance maneuvers were done very conservatively to try to prevent inter-drone collisions.

Many of the issues, especially the communication challenges, will be solved with the updated code implementation as explained in the next section.

Updated code

The firmware that the Crazyflies used to fly in the experiments showed in the paper, can all be found in this public repository. However, the code is based quite an old version the current Crazyflie firmware, as it was forked almost a year ago. The implementation of the SGBA state machine and the P2P broadcasting were not generic enough to integrate this back to the development cycle, therefore the current code is only suitable for the old Crazyflie 2.0.

Therefore, we developed two major changes in the latest firmware which will make it much easier for me (and other ideas as well we hope!) to implement SGBA and the P2P communication in a way that should be compatible with any version of the firmware (and hardware) from here and on. We implemented SGBA as an app-layer and also handled all the broadcast messaging directly from this layer as well. Please check out this Github repository with this new app layer implementation of SGBA.