Lately we have been thinking about and using the Rust programming language more at Bitcraze. In this blog post we will talk a bit about our current use, current experiments and potentially future use and how it will affect our ecosystem.

Rust is a system programming language that has good performance, is reliable and productive. Practically it means that it can be used to run small and fast code (well suited for embedded systems for example), be quite fun to write, and be reasonably sure that if it compiles, it works.

On servers

Over the year we have written and maintained a server system to handle a lot of things related to production and sales. This system is the one generating shipping quote when you order in our store, telling us that there is an order, printing packing lists and shipping labels for the order as well as keeping track of stock and telling us when it is time to order a new batch of product.

This system is used every day and has been invaluable to how we work at Bitcraze. It is mostly implemented as NodeJS micro services.

We have started writing new functionality for it in Rust instead of in a new monolithic service. This has been a great experience, not always easy, but the bonus is that once it compiles there has been almost no run-time error. This has allowed us to gain experience with Rust in an environment that is well documented: servers on PC.

In test rigs

Every manufactured product must be tested: there is no guarantee a board will work when it exits the re-flow oven. This test usually happens in a test-rig that measures and affects various signals on the board (look under your favorite Bitcraze deck and you will see test-points: round pads designed to enter in contact with test probes). Attached to this test-rig is a computer running our test software. We have used a Python-implemented test software for all our products so far and this system started showing its age by being harder and harder to work with and, most importantly, hard to deploy on computers in the factory.

For Crazyradio 2.0, we decided to completely re-write our test software, in Rust of course :-). The design of the test framework is very inspired by OpenHTF: the framework provides the basic architecture of the test and the executor, tests are implemented in Rust and implement all the required test phases. Test statuses are streamed to a web browser as well as to our server (to one of the newer parts of our server system written in Rust). There are two big advantages of using Rust in this application: making sure the test software works reliably and without errors saves a lot of time during manufacturing and helps make sure no bad board leaves the factory. Rust is also awesome to deploy and distribute: the software written on our Linux machine can be compiled for Windows/Mac/Linux on any architecture, no more Python environment to set up!

As for the deployment we actually choose to deploy the test software on a Raspberry pie managed by Balena cloud. This means that we can remotely update the test rig software and we are always sure that the right version is running in production. Rust has allowed that to be painless: we develop on our amd64 PCs and it compiles out-of-the-box and works on the ARM64 Raspberry Pi.

In embedded systems

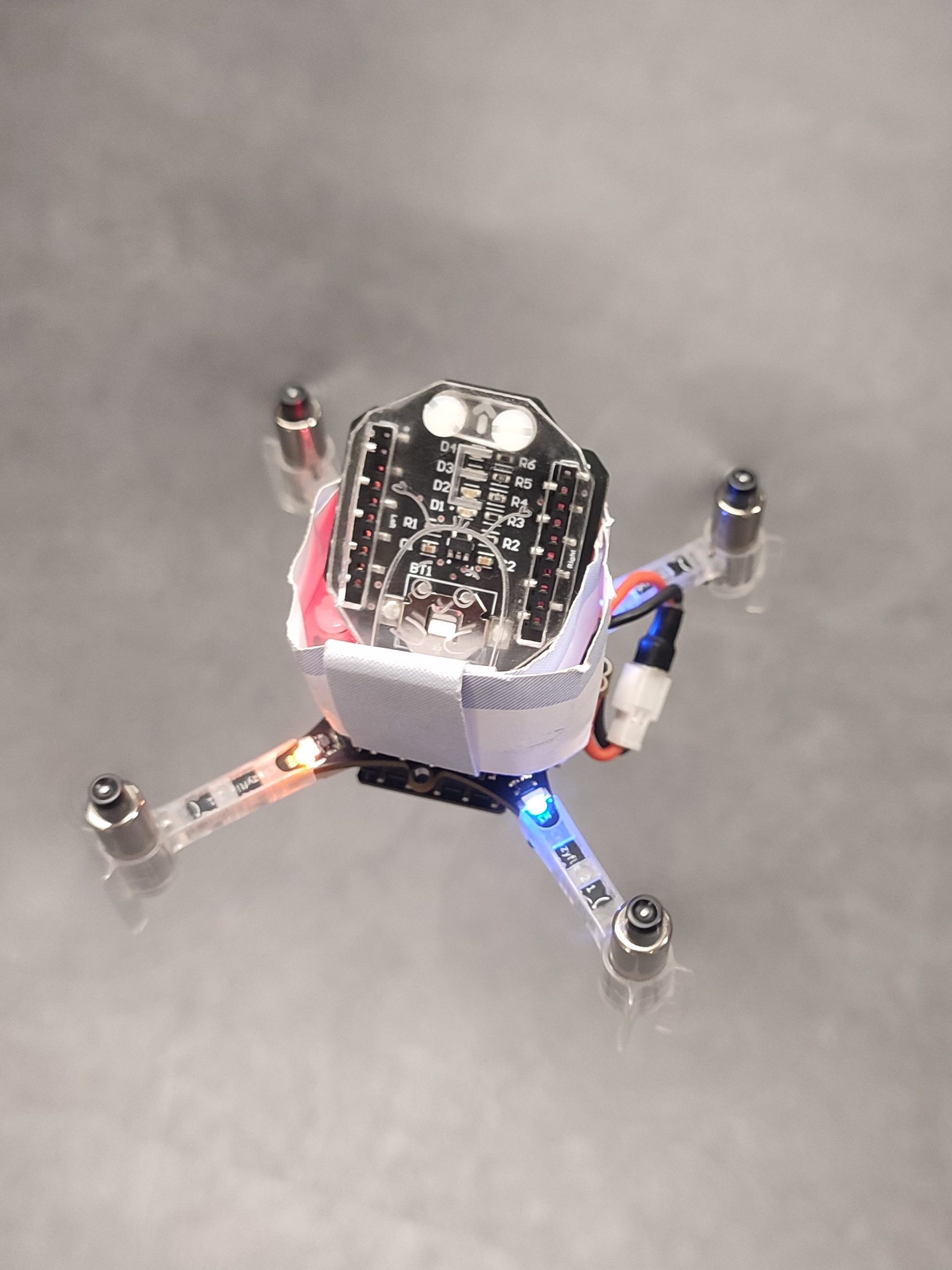

Now we are coming to our more experimental use of Rust, until now on fun-Fridays project but soon on prototypes. We have been playing with Rust on embedded for quite a while: I have re-written the Crazyflie2’s stm32 boot-loader in Rust, we have experimented with Rust on a couple of our ESP32-based prototypes. Embedded systems are never as easy as programming on PC and the way Rust libs are organized to guarantee good usage of the peripheral does not always yield good error messages from the compiler. But, for sure, it does not feel good and it feels very scary to come back to C: the Rust compiler checks so many things that it makes programming fun, with C, any small mistake will bite hard a couple of weeks later.

We have just started working seriously on a new deck (more about it in a future blog post ;-) and we have started in Rust. We do still take that as an experiment: we keep our options open to coming back to C if there is any hiccup. But so far it looks quite good.

In the Crazyflie lib?

That is a future plan, that we have not started to work on seriously at all, but that we are planning for the future. We are planning to write a new version of the Crazyflie lib in Rust with binding to other languages.

According to our experience so far, Rust is safe, fun to write, and very easy to distribute to all the systems we currently support with the Python lib and more. On top of Windows/Mac/Linux, Rust would enable support of our official lib on the web, in embedded systems (ie. ESP32), as well as on iPhone and Android.

The plan would be to have the low level of the lib, ie. communication with Crazyradio and the Crazyflie and subsystems drivers, implemented in Rust. Then binding to Python, C++, Ros, Javascript, … can be made to allow usage of the lib in these languages. This would have the advantage of allowing every current user to use the official lib without having to re-implement their own special-purpose version. On the Python side, nothing would change, in the sense that a Rust-implemented lib can be installed with “pip install cflib” …

Conclusion

This blog post is a request for comments: if you are a user of the Crazyflie and have strong opinions for or against Rust we would like to hear about it. We want to make it clear that we are not planning on porting the Crazyflie firmware to Rust: the Crazyflie is designed as a development platform and we are aware that Rust is not yet as used or well-known as C or Python. However, the firmware running on a deck CPU or in the bottom of the lib would benefit a lot from Rust’s advantages and do not need to be modified so often outside Bitcraze (it is of course always open-source and we encourage contributions :-D).

We will keep you updated if we make more progress on the new deck and the lib, in the meantime we will keep having fun experimenting :-).